Grief, Algorithms, AI, Ethics / Humans + Tech - #57

+ The way we express grief for strangers is changing + Hidden algorithms that trap people in poverty + Can AI fairly decide who gets an organ transplant? + AI, Ethics, Timnit Gebru, Google

Hi,

A lot of interesting articles and happenings this week. Let’s start with how technology is changing how we are grieving online and then get into algorithmic accountability, ethics of AI, and the controversy around Google’s dismissal of Timnit Gebru, technical co-lead of Google’s ethical AI team.

The way we express grief for strangers is changing

The way we are grieving is changing. The pandemic has forced memorials and funerals to move online. Our grief now extends beyond our friends and family that we know in real life to our virtual friends whom we’ve only known online and in many cases, even strangers. Technology has been a blessing and is helping us deal with our grief in ways that would be impossible otherwise [Tanya Basu, MIT Technology Review].

Claire Rezba, a physician in Richmond, Virginia, started an online memorial after hearing of the tragic death of Diedre Wilkes, a mammogram technician, due to Covid-19. In March, Rezba started documenting all the health-care workers who died of Covid-19 and started posting mini-obituaries on her Twitter account @CTZebra.

For Rezba, the notices on her Twitter account are people she becomes close to, watching from afar.

“I don’t know any of these people,” she says, choking up. “But their losses feel so personal.”

In the article, Tanya Basu has listed other examples, such as an online Covid memorial, a virtual scrapbook for people to learn about the lives of those who fell victim to the virus, Zoom funerals, and Instagram memorials for people with AIDS.

This year’s remote life has shown that physical distance doesn’t have to be a barrier to empathy. “There’s a desire to move death to a technological solution to help people meaningfully experience and understand what is quite distant right now,” Pitsillides says. “Millions of people are dying, but mobile phones are a vehicle to make those people more real, to use these spaces to create eulogies, to record and take pictures.”

In Issue #28 of this newsletter, I talked about virtual worlds and how people are replacing reality inside these virtual worlds. Some are now having virtual memorials for their loved ones within Animal Crossing, a virtual world, with many strangers planting virtual flowers for those lost.

Grief is complicated. Especially in a pandemic. By now, almost all of us have lost friends, colleagues, or family members to Covid-19. Our empathy intensifies our grief for strangers and their loved ones.

It’s a blessing that technology in different ways is helping us share our grief and provide comfort even to strangers. It’s not as comforting as a hug, but a huge help at a time when physical expressions of sympathy are difficult and in some cases, impossible.

The coming war on the hidden algorithms that trap people in poverty

Algorithms are pervading our lives and influencing decisions regarding creditworthiness, jobs, healthcare, government benefits, insurance, law, and almost every service we access or receive. Many of these algorithms are owned by private companies that don’t provide explanations on how these algorithms arrive at their decisions.

More concerning is the fact that low-income individuals are affected the most, especially when the algorithms get their decisions wrong. It can push them into poverty and make it almost impossible to recover [Karen Hao, MIT Technology Review].

Low-income individuals bear the brunt of the shift toward algorithms. They are the people most vulnerable to temporary economic hardships that get codified into consumer reports, and the ones who need and seek public benefits. Over the years, Gilman has seen more and more cases where clients risk entering a vicious cycle. “One person walks through so many systems on a day-to-day basis,” she says. “I mean, we all do. But the consequences of it are much more harsh for poor people and minorities.”

The examples are many.

Miriam, a survivor of “coerced debt,” when a partner or family member ruins your credit by accumulating debt on your behalf, is struggling to regain her credit score.

34,000 people were incorrectly accused of fraud when the state of Michigan tried to automate their unemployment benefits system, which led to bankruptcies and suicides.

A family member who lost their job due to the pandemic, was denied unemployment benefits due to failure in an automated system. The family subsequently was sued for eviction after they were unable to pay their rent. And although the eviction will not be legal, it will cause a domino effect for the family in the future as all these algorithms feed off historical records:

While the eviction won’t be legal because of the CDC’s moratorium, the lawsuit will still be logged in public records. Those records could then feed into tenant-screening algorithms, which could make it harder for the family to find stable housing in the future. Their failure to pay rent and utilities could also be a ding on their credit score, which once again has repercussions. “If they are trying to set up cell-phone service or take out a loan or buy a car or apply for a job, it just has these cascading ripple effects,” Gilman says.

Although lawyers are now more aware that an algorithm is at fault, it makes their work much harder, especially when the explainability of how the algorithm arrived at its decision is not transparent. However, many civil lawyers are now organizing around this to be able to represent their clients better.

Fortunately, a growing group of civil lawyers are beginning to organize around this issue. Borrowing a playbook from the criminal defense world’s pushback against risk-assessment algorithms, they’re seeking to educate themselves on these systems, build a community, and develop litigation strategies. “Basically every civil lawyer is starting to deal with this stuff, because all of our clients are in some way or another being touched by these systems,” says Michele Gilman, a clinical law professor at the University of Baltimore. “We need to wake up, get training. If we want to be really good holistic lawyers, we need to be aware of that.”

Algorithmic explainability is crucial when it comes to decisions being made on people’s lives and livelihoods. Unfortunately, the industry seems to be moving towards automation at a break-neck speed without giving a second thought to implementing methods to determine how the algorithms arrived at their decision.

With government agencies buying off-the-shelf algorithms developed by private companies, to automate government services, the problems are being compounded. In my opinion, all algorithms used for public services by governments should be audited, verified, and should be subject to strict regulations requiring algorithmic explainability.

Can AI fairly decide who gets an organ transplant?

Speaking of algorithmic accountability, hospitals and health care organizations are already using AI to determine the severity of cases of their patients and the type of care they receive [Boris Babic, I. Glenn Cohen, Theodoros Evgeniou, Sara Gerke, and Nikos Trichakis, Harvard Business Review].

Consider a recently published study about models used by some of the most technologically advanced hospitals in the world to help prioritize which patients with chronic kidney disease should receive kidney transplants. It found that the models discriminated against black patients: “One-third of Black patients … would have been placed into a more severe category of kidney disease if their kidney function had been estimated using the same formula as for white patients.” While it is just the latest of many studies to show the deficiencies of such models, it is unlikely to be the last.

Ethics has mostly been an afterthought when implementing such algorithms. The authors of the article say that AI and analytics can be used to improve operational efficiency without sacrificing ethical principles if moral objectives and constraints are considered from the outset when designing the models.

An ideal process starts with understanding all of the dimensions of the goal and then trying to find the best way to achieve all of them to the greatest degree possible. It is therefore imperative to develop models and data analytics processes that, from the start, are trying to balance all the objectives, including the ethical considerations.

For the allocation of organs for transplants, this would mean before even beginning to build the AI algorithms or analytics models, you would give ethicists a “clean slate” to articulate what allocation outcomes are considered fair. For example, what percent of organs shall be offered to Black or female patients? Once these questions are addressed and there is a North Star on the horizon, then leverage data, AI, and analytics to design a policy that hits or at least comes as close as possible to these targets.

In the near future, countries and governments are going to face a critical challenge with the Covid-19 vaccines and who should receive them first. Many will likely use algorithms to make those decisions. Let’s hope that they take ethical considerations from the outset to try to make the best decisions possible.

AI, Ethics, Timnit Gebru, Google

As AI entrenches itself more and more in our lives, the incorporation of ethics in AI is going to be of the utmost importance to ensure fairness.

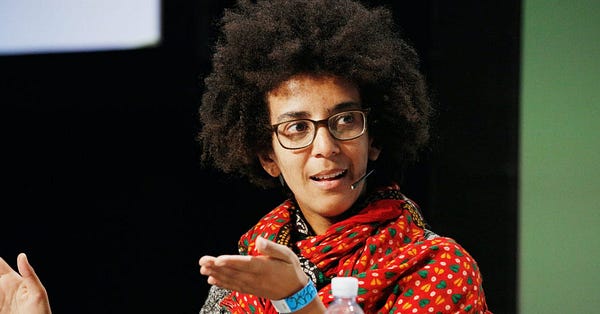

Timnit Gebru is a widely respected leader, among the most respected Black female scientists working in AI ethics research, and technical co-lead of Google’s ethical AI team. She is known for her 2018 paper that she co-authored with Joy Buolamwini that found high error rates in facial analysis technology for women with darker skin tones (mentioned in The dangers of facial recognition technology / Humans + Tech - Issue #33).

On Wednesday, she was fired abruptly by Google.

Central to the conflict is a new paper that Gebru and her co-authors wrote that she had submitted for review before publication. Google asked her to retract or remove her name from the paper. Gebru voiced her frustrations in an email to an internal group, Google Brain Women and Allies. Gebru asked Google for certain conditions to be met for taking her name off the paper, and if they couldn’t meet the conditions, they could “work on a last date.” Google refused and fired her with immediate effect.

Casey Newton published the email from Gebru to the Google Brain Women and Allies group, as well as a response from Jeff Dean, head of Google AI, in his newsletter, The Platformer.

In an interview with WIRED, Gebru said that the paper addressed recent advances in AI language software and how the models can replicate biased language on gender and race found online. She said that she felt like she was being censored by Google:

Gebru says her draft paper discussed those issues and urged responsible use of the technology, for example by documenting the data used to create language models. She was troubled when the senior manager insisted she and other Google authors either remove their names from the paper or retract it altogether, particularly when she couldn’t learn the process used to review the draft. “I felt like we were being censored and thought this had implications for all of ethical AI research,” she says.

Karen Hao at MIT Technology Review obtained a draft of the paper that Gebru co-authored and gave a summary of the paper’s findings.

Titled “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” the paper lays out the risks of large language models—AIs trained on staggering amounts of text data. These have grown increasingly popular—and increasingly large—in the last three years. They are now extraordinarily good, under the right conditions, at producing what looks like convincing, meaningful new text—and sometimes at estimating meaning from language. But, says the introduction to the paper, “we ask whether enough thought has been put into the potential risks associated with developing them and strategies to mitigate these risks.”

It is unclear as of yet whether Google is justified in their actions or not.

However, it doesn’t look good for them that current and former employees are disputing Jeff Dean’s explanations.

Nicolas Le Roux, a Google AI researcher in the Montreal office:

William Fitzgerald, a former Google PR manager:

More than 1,200 current Google employees and 1,500 academic researchers condemn the firing of Gebru [The Guardian].

Over 1,500 Google employees and over 2,000 academic, industry, and civil society supporters have signed a letter [Medium] from an employee group called Google Walkout For Real Change, demanding answers from Jeff Dean about why the company allegedly attempted to censor Gebru's research and fired her.

This is not a good look for ethics in AI or Google, one of the world’s biggest AI companies. Azeem Azhar summarizes the whole situation perfectly.

Quote of the week

“This is happening across the board to our clients. They’re enmeshed in so many different algorithms that are barring them from basic services. And the clients may not be aware of that, because a lot of these systems are invisible.”

—Michele Gilman, clinical law professor, University of Baltimore, from the article “The coming war on the hidden algorithms that trap people in poverty” [MIT Technology Review]

I wish you a brilliant day ahead :)

Neeraj